This is a short “Technical Notes” article that I wrote for the Australian Wildlife Sound Recording Group’s Journal, AudioWings, a couple of years ago. It is intended as an introduction to what phase or polarity is in the context of nature sound recording. Thanks to Sue Gould, the editor of the journal at the time for her suggestions and feedback, and to the Australian Wildlife Sound Recording Group for being a great bunch of people. You can find out more about the Australian Wildlife Sound Recording Group at https://awsrg.org.au/

A lot of modern audio recorders and software have a Ø or phase setting, but as nature sound recordists, when do we need to consider using it? The good news for a lot of people who go out field recording with a single microphone is that it doesn’t really matter too much if you have your Ø/Phase setting on your recorder on or off if you are dealing with a single microphone, and I suggest that it is good practice just to leave it turned off. The Ø/Phase setting becomes more of a consideration when dealing with multiple microphones, either to mix together, or for stereo or surround recordings.

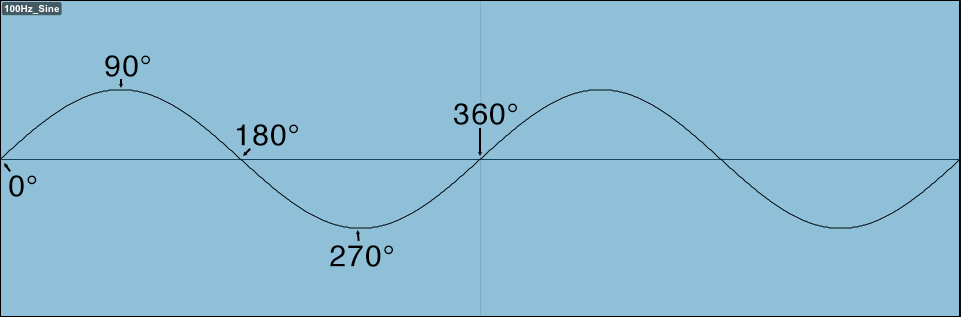

Firstly, let’s touch on what phase and polarity are. It is easiest to look at a simple sine wave to explain this. A sine wave represents a circular motion; or for audio, a pure audio tone. A pure tone is a sound occurring at one frequency only, with no harmonics. It has a waveform that looks like Figure 1.

The waveform is marked with some indicators for degrees of phase. Note that 360° relates to a full rotation of a circle which corresponds to a full wavelength (?) of our sine wave.

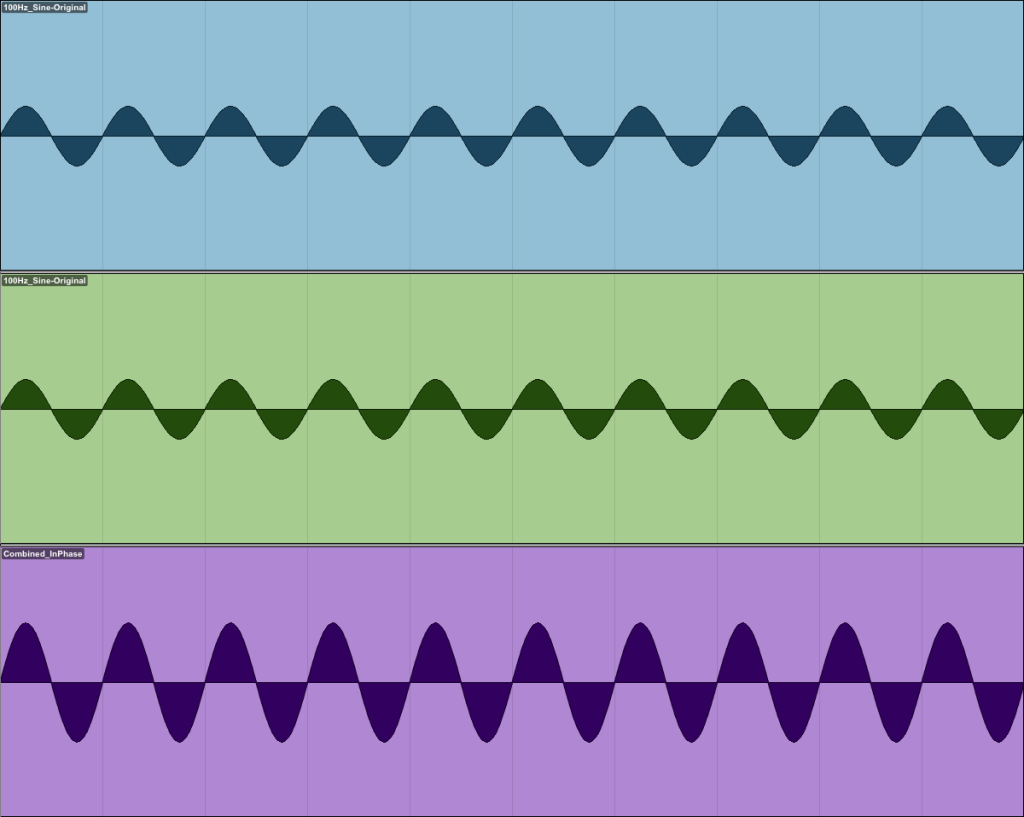

Phase relates to the timing of a wave. If we have a duplicate of our original sine wave that goes through it’s cycle of positive and negative values with identical timing, then we say that these waves are ‘in phase’ with each other. When two duplicate sine waves are summed together, the values add together, with the result being a 6 dB higher amplitude (i.e., a doubling) in the combined wave than in the single original wave (Figure 2).

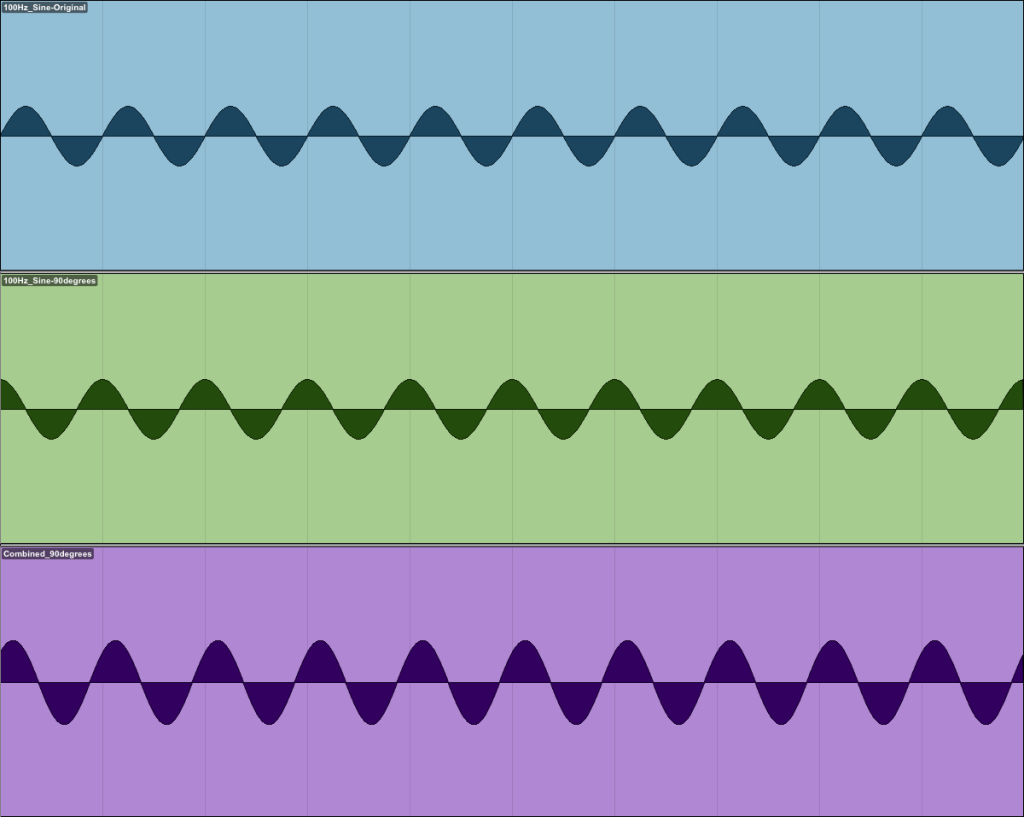

Now consider if one of these two sine waves is a little out of time with the other. If we push the duplicate wave out of time by a quarter of a wavelength, then the two waves are 90° out of phase with each other. When these two waves are summed the values still add together. Now however, because some values are in the positive and some are in the negative, we get a combination of addition and subtraction, or cancellation of our values. This still ultimately results in a higher amplitude waveform than the original, but only a 3 dB boost (Figure 3).

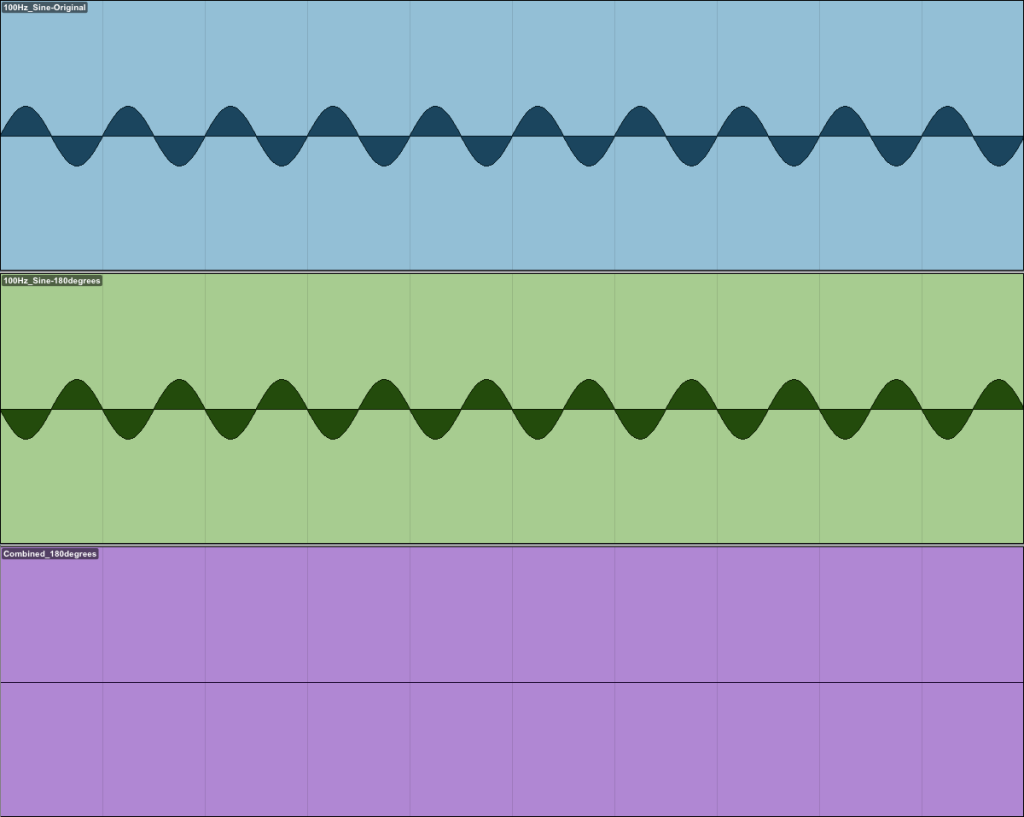

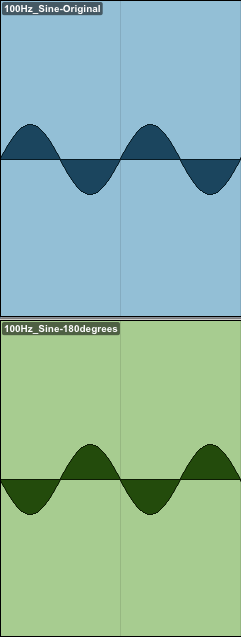

Now if we push our duplicate sine wave back by a further 90° so that it is 180° out of phase with the original wave, we get the completely ‘out of phase’ condition. If we sum these two waves together we actually get a complete cancellation of our waves (Figure 4).

The reality is that when out in nature, we are never recording pure sine waves. So how does phase relate to a more complex waveform like what we might actually encounter in the wild? Phase gets more complicated with complex waveforms, because phase is relative to time and frequency.

Let’s say we set up for recording a lyre bird, in mono, but we set up a single microphone close to the lyre bird mound, and another microphone a couple of metres back into the bush away from the mound to create a bit more ambience (and in case the lyre bird gets too loud for the close microphone to handle without distortion). In this instance, the sound from the lyre bird on the mound takes longer to reach the more distant microphone than the close microphone, and so there will be timing/phase differences between the two received signals. If we combine the signals at the recorder or in post-production, we might find that we get phase cancellation of some frequencies which can make the lyre bird sound strange and alien, even robotic and processed sounding.

To combat the effects of phase cancellation, there are a few things we can try. One is to turn on the Ø/Phase setting for one of the channels to see if it combines better. This can be done, either on your recorder or in your software. In effect, the Ø/Phase setting inverts the polarity of the audio signal, which is to say that it “flips” our waveform over by 180° so that the part of our waveform that was going into the positive is now going into the negative and vice versa (Figure 5).

Technically, this Ø/Phase setting should be called ‘polarity’, but it has the same effect as changing the phase of every single frequency component by 180°. Some hardware and software manufacturers use the term ‘phase’ for this, and some engineers and recordists might refer to ‘flipping the phase’, which might be better referred to as ‘inverting the polarity’.

The Ø/Phase setting can be used when attempting to achieve better summing of signals from two or more microphones where there is a difference in time of arrival of our sound to each microphone. It may also be useful in circumstances where the two microphones you are using are wired out of phase with each other, or facing in opposite directions to each other.

When recording with two or more microphones using non coincident techniques, such as spaced or A-B stereo, some phase difference between signals will occur. Because of the way our brains process audio signals, this phase difference can increase the sense of spaciousness in our recordings. There can be a trade-off, however, in that there will be some phase cancellation (amplitude reduction) at some frequencies if it is mixed down to mono. However we don’t usually need to use the Ø/Phase setting in these situations, even though a basic consideration of phase is useful. For example, while out recording during the recent AWSRG Workshop at Smiths Lake recently, I realised that I had accidently turned on the Ø/Phase setting for a few of my recordings. This resulted in recordings that sounded a little strange and unusually wide when listening back on speakers. This felt odd on my ears, and would cause some phase cancellation issues when listening in mono. Fortunately this was an easy fix back at the studio by using the Ø/Phase setting in a plug-in in my chosen audio software, and is one of those few times where I’d suggest it is OK to ‘fix it in post’.